Yes’ Steve Howe on ‘The Quest’ and Recording Without Chris Squire

The Yes lineup has always ebbed and flowed erratically — at this point, fans have grown used to such long-distance runarounds. But The Quest, the prog-rock band’s 22nd LP, marked a more significant shift than usual: It’s their first without the signature bass growl of cofounder Chris Squire, who died in 2015.

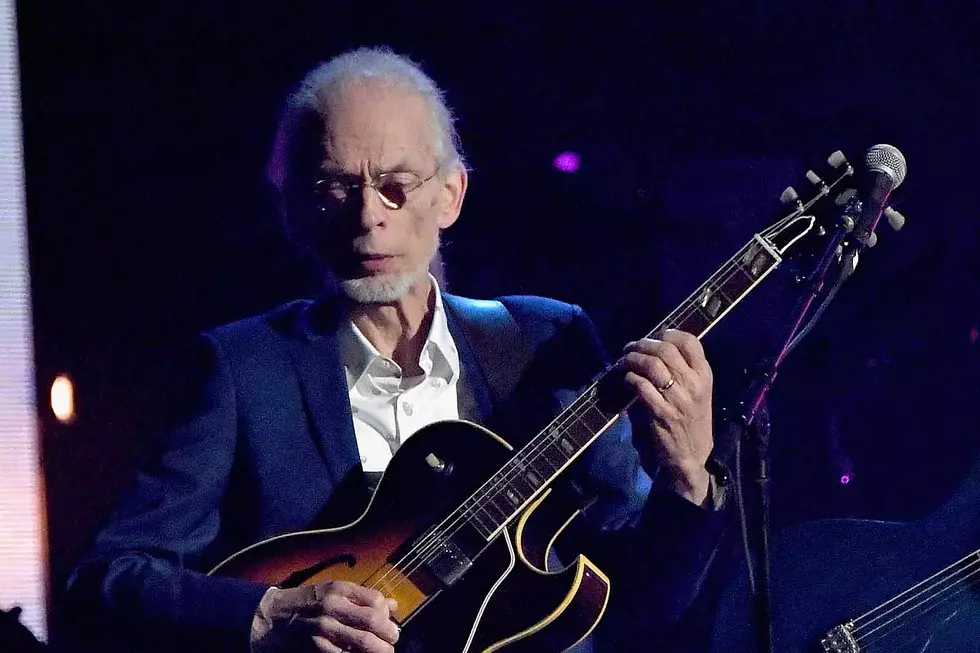

There was pretty much only one natural fit for a replacement: multi-instrumentalist Billy Sherwood, a close Squire collaborator who played in the band during the ‘90s. And that steady presence offered Yes a huge lift, both sonically and spiritually, on their first album since 2014’s divisive Heaven & Earth.

“We didn’t over-discuss it,” Steve Howe tells UCR, reflecting on having to fill those massive shoes. “But we were doing something that we hoped Chris would’ve liked. In our wildest fantasy, we’d send Chris a copy, and he’d say, ‘Fuck me, you did a pretty good job!’ That would be a really great payoff.”

We’ll never know Squire’s final verdict. But Howe — the album’s sole producer — is still beaming about The Quest, highlighted by several extended instrumental sections and a few unobtrusive orchestral arrangements by Paul K. Joyce. Crucially, he says, the band atmosphere was more spirited and focused than any of their previous five records, which he describes (somewhat playfully) as “a headache, a toothache and a stomachache all at once.”

Howe tells UCR about his shift to self-production, Squire’s irreplaceable presence, the lessons Yes learned from 2001’s Magnification and what went wrong on Heaven & Earth.

Some of the new album, at least early on, was assembled through file-swapping. You’ve been doing that kind of thing for years — last year, you talked to me about how you used to send the actual physical tape to people and have them record on it. But do you find that more challenging, not being in the same room with the people you’re writing with?

There’s a balance where you can look back and say, “Some of the old methods were kind of good. But [sometimes] you’re in there, and everybody’s like, “How come you’re late?” [Laughs.] That kind of stuff went on all the time. There was a lack of efficiency, unless the producer was very strict. Like you said, there’s been a lot of this going on, and fortunately for us there was a plus side to experiencing the historic norm of recording. We chose this guy I’ve been working with for like 25 years, Curtis Schwartz. [His studio] was like our headquarters — basically Jon [Davison] and I started there with a couple days at the end of 2019. I said to him, “I’ve got a lot of songs.” We worked through a few of mine and some of Jon’s, and we got an idea that this was going to work with me producing. I said to the guys, “I’d like to produce, and that’s it. Yes or no kinda thing. [Laughs.] They said “yeah,” so that went ahead. I tried out my concept, which was the HQ studios and file-sharing. Fortunately Jon has been in England a great deal, and Geoff Downes lives in Wales, which is quite near my studio in the west country. He could come down and do actual keyboard sessions in the room, and Jon could do vocals in the room. We had just enough of that to keep ourselves satisfied. But on the other hand, the good side of it from the producer’s point of view is that I was able to steer. Not only were they willing to let me, but there weren’t the daily arguments about “Ah, you’ve taken that bit out” or “Why do you want to change that word?” I just kind of went for it and said to the guys, “I’ll do things on some tracks, and other tracks will come at me and I won’t need to do a whole lot.” Some of them did need my perspective of saying, “I like the material, but let’s rearrange it with beginnings and endings; let’s develop this.” I was able to do a lot of development sessions where the guys weren’t there but their songs were. I could help to bring things to it — the only thing I had to do was knock it out. I’ve said on a few occasions that if your producer isn’t coming up with good ideas, get another one! [Laughs.]

I think a producer’s world is very much about the right decisions being made and the right plan — finding the solution to every problem. He’s got to get on with it. I had that momentum because I’ve done all my solo albums and have been part of the Yes production team — when it said “produced by Yes,” it was produced by me, Eddie Offord, Jon [Anderson] and Chris [Squire]. Those probably more than Rick [Wakeman] and Alan [White] or Rick and Bill [Bruford] because they weren’t writers in the sense of songs; they were more instrumentalists. So all in all, when we look at The Quest now, it was good timing — there’s nothing good about the pandemic, for God’s sake. But the timing allowed us to get a strategy, get a methodology, to allow us to be able to do it.

Listen to Yes' 'The Ice Bridge'

You’ve talked a lot previously about the challenges of recording Heaven & Earth. What went wrong with that album? What part of the process was so difficult?

I had held everybody back, and then we did start, and the disappointing thing was we gave ourselves quite a window to record, and then a tour approached. We really wanted to do the tour — we weren’t going to pull the tour. My most reasonable complaint would be that some of the band felt we could mop up the record and finish it and then go to Canada. And I said, “No way. Let’s go to Canada, and even if we can’t come straight back to it, let’s come back to it later in the year and sort it out then.” It was, “Oh, no, no, gotta finish." This reason, that reason. We should have done it differently, and we didn’t. We worked with [producer] Roy Thomas Baker in the late ‘70s on the famous Paris tapes, and it didn’t work out. We realized about halfway through [Heaven & Earth] that we didn’t have the right team. That was really difficult. That’s why we could have taken the album away, rested it and really sorted it out later. That’s about all I can say.

It’s very heartening for a lot of fans to see Yes return to a more ambitious place with some of the longer, more ornate pieces. Is there any reason for that shift — just a natural reaction to the last album? Did it have anything to do with you serving as producer?

This is a cliche, but the last five albums from Yes before The Quest were very problematic — they were a headache, a toothache and a stomachache all at once. That’s a bit of an exaggeration, but in some respects they were problematic for one reason or another — not one consistent reason running through it. But I was always holding the guys back, saying, “Are you sure we’re ready for this album? Have we got the stuff?” I was always the last one to agree to those albums going ahead, as far as I can remember. They always wanted to do it sooner. That was one aspect of it. But certainly the accumulation of material was vital. There [was a clear motivation to] this album: a drive, an enthusiasm. The biggest word is … happiness. [Laughs.] I didn’t want to do another album that wasn’t happy. My solo projects are always happy affairs. Everybody is happy working with me, and they get paid, and they get what they deserve. They get the split if they write. That’s what happened on this album. It's astounding that we can say that with all honesty — there weren’t any big gremlins on this album.

It’s satisfying to hear you guys go to a more expansive place.

Jon wrote on Geoff's music [for] the song “A Living Island.” I said, “This is a classic, epic kind of anthem to this idea [of the pandemic], but no more.” [Laughs.] We don’t need another song about COVID — when you look back at the album, you’re going to be listening to a bunch of guys moaning about the pandemic. But “A Living Island” was such a beautiful, romantic, epic story about being in Barbados and "who would you rather be with than somebody you love?" It was perfect. But that’s when I said, “That’s it. No other songs about this thing.” [Laughs.]

Listen to Yes' 'A Living Island'

I really enjoy the track “Dare to Know,” which bridges the gap between the more symphonic, grandiose Yes sound and something a bit more simple and radio-friendly.

The one thing about that song that really does surprise me is that I can’t remember [another] song I wrote that got to where I wanted it to [this] extent. The sort of R&B idea of the choruses, the verses that are more subdued. The whole thing was delightful for me. First of all, Jon saw what the song was — that was the important thing. And we did the duet vocals that we have on several tracks. We sing together like a lot of great bands do — the guys sing together! [Laughs.] That was a key thing.

The orchestra is crucial to that one.

That was the first track where I said, “Guys, do you think we should [incorporate] an orchestra? Instead of an orchestral album, which I don’t want to think about doing. What I wanted to do was bring in an orchestra occasionally to show the breadth of our love for the textures [it] can bring — as much as a Hammond organ or a Gibson guitar or whatever. These are all known quantities. I asked Paul K. Joyce, who did my album Time, to do some arranging on that song, and I said, “Here’s the bit: When we sing ‘rearranging, rearranging,’ you’re off. You go in there.” Paul wrote that synopsis, almost, of the themes. One of the keys to that song which gives me a certain buzz, being a bit of a chord maniac: Most times you hear the theme that I play, it’s in a different chord or structure. One time, it’s no chords at all — it’s a drone. It’s major sevenths; another time, it’s a mixture of jazzy chords. Later in the song, you get the tune again, and it’s flatted fifth, and then you get back to the major sevenths. I can’t help being excited that you and other people like it because it’s so much of what I wanted to do. Paul said to me, “We can do this. We’ve got the arrangement worked out, but you can do more in the session than what you’ve got on ‘Dare to Know.’” I went, “Ahhh, so we can have the orchestra more!” Instead of what happened with things like Magnification or Time and a Word, which was just a swamp of stuff, we picked strategic moments. We found a happy medium of having orchestral work but it not sounding like an orchestral album. I haven’t heard many [such albums] that work.

Listen to Yes' 'Dare to Know'

Magnification recently turned 20 — it’s a very underrated album.

I’ll tell you something about Magnification — we did our backing tracks and gotten solos on and everything, and Larry Groupe did the arrangements, and they put them on. Tim Weidner was our engineer through my choice — I chose Tim because he worked on my album Turbulence, and he was one of Trevor Horn’s top people. We got him over there, and he said, “What have you gotten me into here?” [Laughs.] I said, “Well, it is Yes, so it’ll be a partial nightmare at times. But we’ll get through it.” One day he walked out of the control room, and he was standing outside, and he said, “You told me it would be like this!” All that was an aside, but what I wanted to tell you: When those mixes came back, I couldn’t hear myself — “Is there a guitar on this, or did they actually take it off?” It was swamped with orchestra. Much to the grievance of the other members, I said, “Stop! Remix! Here’s what you’ve got to do.” And I did a list of every tune, and I pointed out — “At like 10 seconds, there’s a guitar that does something quite important here. At three minutes, that little guitar, can we hear it, please?” So we went through the whole album, and I got them to adjust it. I couldn’t do it myself because I was in another country. But I gave them sufficient notes to keep them busy for a long time making that record like you hear it now.

It’s very surreal listening to a Yes album without Chris Squire, although Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe is essentially a Yes album in all but name. You guys have already been touring with Billy, who’s doing an incredible job with impossible shoes to fill — but was it emotional working on these songs without Chris?

I don’t really think Chris ever went away from us. It’s not like he passed away and we forgot about him. We couldn’t! We wouldn’t! We would never want to. The Quest has only been possible because of the incredible teamwork that we did [since Billy joined], and also before then in preparation with [keyboardist] Geoff [Downes] coming in. We didn’t over-discuss it. We just knew we were doing something that we hoped Chris would’ve liked. In our wildest fantasy, we’d send Chris a copy, and he’d say, “Fuck me, you did a pretty good job!” That would be a really great payoff. But that’s not possible. But I think Billy is the one person — ABWH had Tony Levin, who is a fantastic bass player, and it taught us a lot of things working with him. Billy has been in Chris’ shoes, and he admires Chris so much. He’s such a Chris fan. We could be at a soundcheck, and if I play a line from a song we don’t play, suddenly Billy’s playing with me. He’s such a wealth of knowledge about Chris’ playing, and I think that’s what our fans have come to realize: Billy’s not some kind of stand-in stooge. [Laughs.] He’s a guy who’s dedicated most of his career to playing in that style. His love of Yes is notorious, and he’s been in the band before in what I call the pre/post-millennium days. It’s very interesting: As we got more and more tracks ready [for The Quest], we were holding them back a bit, and then we started sending them to Billy to get his input on them. In a way, I think Billy subconsciously had the idea of “If I do it like this, when [Alan does] the drums, it’ll be like this.” Some amazing arrangement ideas came from after Jon, Geoff and I had played. Billy added the bass, and the drums went on, and they accentuated and punctuated Billy’s playing so much that it was like a tribute to Chris. Like “Sister Sleeping Soul” — the way he plays that is a great example of how he’s learned from Chris what Chris might have played. The way he sits out of certain beats — much of it is intuitive with Billy because of his love for Yes, and in particular Chris.

Top 50 Progressive Rock Artists

More From KKTX FM