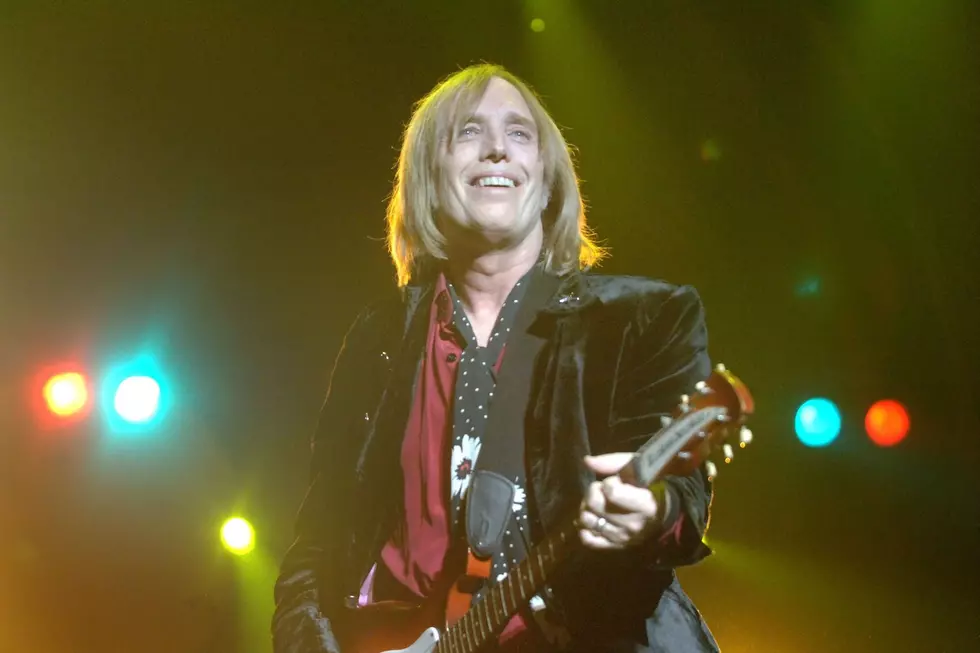

How Tom Petty Caught ‘Full Moon Fever’ With Jeff Lynne: Exclusive Book Excerpt

Tom Petty had several key collaborators throughout his career. And few were more crucial than Los Angeles.

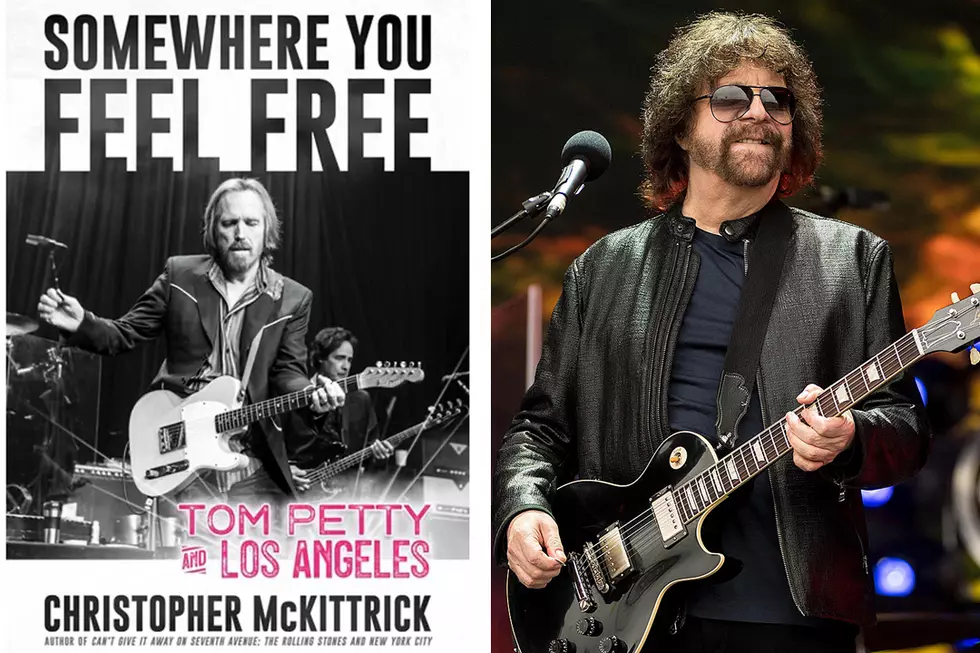

In Christopher McKittrick's upcoming book Somewhere You Feel Free: Tom Petty and Los Angeles, the author explores Petty's relationship with his longtime home city — including the venues and many legendary musicians (like George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Stevie Nicks and Johnny Cash) who crossed his path there.

"From the earliest Heartbreakers concerts in Los Angeles at the legendary Whisky a Go Go and the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium to the band’s final concerts at the iconic Hollywood Bowl, Petty aimed to continue the tradition of the Southern California rock 'n' roll of his musical heroes like the Byrds and Buffalo Springfield in his own fashion," reads a press release for the book. "At the same time, Petty’s career often coincided with seismic shifts in the music business, indicated by Petty’s famous refusal to back down in the face of label management, industry conventions and the changing courses of platforms that helped make him a superstar, like rock radio and MTV."

Somewhere You Feel Free, available to pre-order now, is out Nov. 17 via Post Hill Press. In the exclusive excerpt below, McKittrick recounts the origins of Petty's first solo project, the 1989 blockbuster album Full Moon Fever, in exacting detail. The initial spark, as the author notes, was the singer-songwriter's casual first meeting with Electric Light Orchestra's Jeff Lynne, who went on to co-produce the record.

Chapter 6

"Wonder What Tomorrow Will Bring"

George Harrison had not released a new album since 1982’s commercially unsuccessful Gone Troppo, when he approached Electric Light Orchestra multi-instrumentalist Jeff Lynne in late 1986 about collaborating on new music. Lynne, who had self-produced or coproduced most of his own releases and had coproduced two albums for Dave Edmunds (1983’s Information and 1984’s Riff Raff), had long been alternately praised and criticized for creating music in the tradition of the Beatles. Depending on the critic’s point of view, Lynne is either a brilliant musician who proudly wears his Beatles influences, or little more than a Fab Four copycat whose production work sounds like he learned all the wrong lessons from George Martin. But in Lynne, Harrison had met something of a kindred spirit who understood and appreciated Harrison’s musical influences and sensibilities and, perhaps more importantly, his humor. The two collaborated on production of Harrison’s comeback album (with Lynne also cowriting three of the album’s songs) over the first half of 1987. The result was perhaps Harrison’s finest album since 1970’s All Things Must Pass. Released in November 1987, Cloud Nine became one of Harrison’s most commercially successful albums and produced his first #1 Billboard hit single since 1973 with “I Got My Mind Set on You.”

Though Cloud Nine would be the last solo album that Harrison released in his lifetime, the collaboration with Lynne would inspire Harrison’s desire to collaborate again—much like Petty, Harrison was comforted by the idea of being in a band.

Shortly after the Cloud Nine sessions concluded, George Harrison and Jeff Lynne attended the Dylan and the Heartbreakers concert in Birmingham, England, and the subsequent four-night run at the Wembley Arena in London that ended the Temples in Flames Tour, going backstage to hang with the band after the shows. This is where Petty met Lynne for the first time. Then, by chance, Petty and Lynne met again a month and a half later in Los Angeles. As Petty recalled in Conversations, “It was Thanksgiving Day. I was at the house in Beverly Hills, and some people were coming over. And I like to have softball games. And so I was going to have a softball game at the house. But I didn’t have enough mitts to play ball. So I was going to drive down to the Sav-On in Beverly Hills and buy a dozen ball mitts so everybody could play ball. ... So I’m at the traffic light, and I look over to my left, and there’s Jeff Lynne. Who I’d only just recently seen in England. So I honked my horn, and he turned around, and we pulled over. And I said, ‘Wow, what are you doing here? And I love that album [George Harrison’s Cloud Nine]; the album’s great.’ He said, ‘I’m working with Brian Wilson.’ And he said, ‘Where do you live?’ I told him where I lived, and he said, ‘That’s weird. I live really close to there. So we should get together.’” Lynne’s work with Wilson resulted in “Let It Shine,” a track on Wilson’s 1988 self-titled solo album.

In the Tom Petty: Going Home documentary, Lynne remembered the meeting differently, saying, “I was driving in Beverly Hills and this horn kept blowing. And I thought, ‘Who the hell’s that?’ And it was Tom. He was going, ‘Pull over. I wanna have a word with ya.’ We pulled over and he said, ‘Oh, I really like what you did with George’s album. Do you fancy doing something together?’ I said, ‘Oh, that’d be nice, y’know.’” Regardless of how it happened, the two were keen on collaborating on music.

Less than a month later, Petty and Lynne had yet another chance encounter—this time in the Valley—that brought another key figure back into Petty’s life for the next few years. Petty remembered in Conversations, “I was with my daughter Adria, and we were out Christmas shopping. We had driven over to Studio City, there was this one restaurant there on Ventura called Le Seur, a French restaurant that was a really good restaurant. ... It was kind of our special night restaurant. I pulled in the parking lot and we came in. I sat down in my chair, and the waiter came over and he said, ‘There’s a friend of your’s [sic] here and he’d like you to come over to the table.’ And that’s all he said. I said, ‘Oh,’ and I got up and walked around—there was kind of this private dining room — and as I walk in, there’s George [Harrison]. And he was having lunch with some people from Warner Bros. And Jeff. And as I walked into the room, Jeff was writing my number down for George. And George said, ‘How strange, I’d just gotten your number and somebody told me you’d walked into the restaurant at the same time.’”

Harrison would follow Petty and Adria home to the house Petty was renting. According to Petty: The Biography, Harrison strummed “Norwegian Wood” on a guitar and joked with Petty by asking him, “You know this one, don’t you?” It would mark the beginning of several collaborations between Petty, Harrison, and Lynne over the next several years, and a friendship between Petty and Harrison that would last the rest of Harrison’s life.

In the new year, Petty and Lynne got together to work on what was initially planned to be a series of demos. Since Lynne preferred the comfort of a home studio, and Petty’s Gone Gator One was out of commission while his house was being rebuilt, they convened at Campbell’s home studio in Woodland Hills, which the Heartbreakers had first utilized to record parts for Let Me Up (I’ve Had Enough). Campbell described his studio to Musician in 1990 as, “Just a bedroom with a 24-track Soundtracs board. If you get three guys in there you’re bumping elbows. It’s real funky, all the wires are everywhere. The main thing is, I try to keep all the wires real short. A lot of studios are designed cosmetically — they run the wires through the walls so you can’t see them, but then there’s miles of wires between the microphone and the board. I think one reason my studio sounds good is because it’s so direct.” Petty, Lynne, and Campbell performed most of the instruments during the sessions. To play drums, Petty called in Phil Jones, who had played percussion on Hard Promises, Long After Dark, and Southern Accents, and had toured with the Heartbreakers during the first half of the ’80s.

As for how the sessions morphed from recording demos to recording an album, Petty would later tell the Orange County Register, “I wasn’t in the mood to make a record. I wasn’t even thinking about making one. We thought we could do it real fast. I told the Heartbreakers, ‘Look, I’m going to make a record’ and they weren’t planning to do anything at the time. I said I could be done with it in a few months. Of course, I wasn’t.”

Unsurprisingly, the other Heartbreakers were less than enthused about Petty and Campbell working without them on what became a full record. At the time the album was released, Petty told BAM, “They weren’t in love with the idea when I told them. They were pissed off at first, to be honest. But they’ve been pretty big about it.” In 2014, Tench spoke to Rolling Stone about that period and shed some light on how the Heartbreakers took the news, revealing, “I was pissed off and hurt. I was also worried he’d split up the band because there was conflict within the group at that time. There wouldn’t be anybody coming to blows, but Tom and Stan [Lynch] would have disagreements, and Stan would leave the band, or get fired, and then come back less than a week later. Stan was always worried that Tom would go [solo], or just grab Mike and pack up. So when he did that, that’s how it felt. I was also pissed by the way I found out about it. We were supposed to make a Heartbreakers record. I called the main guy on our crew about a week before we were supposed to start to ask what time we were coming in. He just said, ‘Uh … ummmm.’ He hemmed and hawed and finally told me they were making a solo record. Nobody told me. ... So that’s one side of the story.” However, Tench also understood how the decision helped the band both personally and professionally and copped to some personal responsibility for Petty wanting a break from the Heartbreakers, adding, “The other side of the story is that I was out of my mind on cocaine and alcohol. I was a very high man and deeply troubled with drugs and alcohol, so I thank Jeff Lynne. I had nothing to do…so I got to go to rehab, and it saved my life. Also, hell, I’d been doing session work for years by that time. Why the fuck shouldn’t Tom go play with someone else and have fun too?”

As Tench noted, for much of the ’80s, all of the Heartbreakers had been working as session players when not recording or touring as a group, with each Heartbreaker having developed an impressive resume of work outside of the group — particularly Tench, who by the end of 1990 had appeared on albums by U2, Elvis Costello, Warren Zevon, the Replacements, Jon Bon Jovi, Hall & Oates, Carlene Carter and Darlene Love.

Of course, none of them had recorded solo albums, and since Petty was the frontman, his solo album could be construed as the first steps of a breakup far more than any of the Heartbreakers contributing to a Stevie Nicks or Don Henley session.

Of all the Heartbreakers, Lynch appeared to take the news of Petty’s solo album most personally. In a 1991 feature in Rolling Stone, Lynch said he was summoned to Los Angeles to play on the album only to wait around until a “third party” told him that he wouldn’t be playing on it. “At that time I thought, ‘Well, fuck me.’ I mean, you know, call me up. ... I thought they were shits who were not even man enough to tell me,” he recalled. “But about a year later I realized they were embarrassed. We’re old friends. How do you call an old friend and say you don’t want him at the wedding?” Afterward, Lynch would relate playing Petty’s solo songs on tour to feeling like he was in a cover band, which Petty took as an insult. Of course, like Tench, Lynch wasn’t just waiting around for Petty’s calls. In addition to working as a session drummer, Lynch performed, coproduced, and cowrote three songs on Don Henley’s third solo album, The End of the Innocence, including the Top 40 single “The Last Worthless Evening.” (Campbell also appeared on the album, cowriting and performing on another Top 40 single, “The Heart of the Matter.”)

Though Campbell was a key player in the solo album sessions, he understood the anger from the other Heartbreakers. In 1989, he told Newsday, “Yeah, of course there was some resentment. How would you feel if your wife went out on a European vacation with another guy? But I think having gone through it, everybody realized that it was necessary to keep the band from getting stagnant. We’re mature people. We know that being a great band is not being on the same bus hanging out with the same five guys for twenty years. We can grow without having to break up.”

Tom Petty Albums Ranked

More From KKTX FM