To Slowly Go Where No Man Has Gone Before: In Defense of ‘Star Trek: The Motion Picture’

The poster for Star Trek: The Motion Picture is so dramatic. The faces of William Shatner’s Captain Kirk, Leonard Nimoy’s Mr. Spock, and Persis Khambatta’s Lieutenant Ilia refracted through a rainbow spectrum of light. That image promises excitement beyond imagination. Adventure! Passion! Every color under the rainbow!

So why is the film so ... beige?

Look at that; not a single primary color on screen. The original Star Trek television show was so visually dynamic, with splashes of bright reds, blues, and yellows. Star Trek: The Motion Picture is the opposite. It’s like an explosion at a milk factory. It’s Star Trek: The Wrath of Khaki. (According to the Star Trek: The Motion Picture Blu-ray commentary, director Robert Wise felt the classic Trek uniforms looked “garish” on the big screen and decided to change them.)

I suspect that’s one big reason why Star Trek: The Motion Picture is widely regarded as one of the worst Star Trek movies. It is also, somewhat perversely, one reason I like it more than almost anyone I know and find myself drawn back to it over and over again, perpetually caught in its hypnotic, tractor-beam-like pull.

With hundreds of millions of dollars on the line, blockbuster filmmakers typically have to play it safe, catering to the masses with simple stories and messages. Star Trek: The Motion Picture didn’t do any of that. True to Captain Kirk’s famous catchphrase, Star Trek boldly went from television to film with grandiose ambitions. Who spends the equivalent of $115 million in 2016 dollars to alienate audiences with tortoise-like pacing, philosophical musings, and psychedelic imagery? With Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Paramount Pictures did. Even its subtitle suggest towering aspirations. This isn’t a movie, it’s a motion picture.

Where the original Star Trek television series (and most of the films that followed The Motion Picture) were lively and colorful, ST: TMP was deliberate and contemplative. Trek finally made the jump to the silver screen in large part because of the wild financial success of the original Star Wars, but TMP feels nothing like the original Star Wars. Moody, methodical, and downright depressing at times, Star Trek: The Motion Picture is as much a rejection of the Star Wars sci-fi model as a space epic made in its wake. The results are much closer in tone and spirit to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey; a thoughtful consideration of a possible future where technology enables mankind to encounter (and join with) an evolved alien consciousness.

The plot isn’t a huge departure from classic Trek; the crew of an updated Starship Enterprise must confront a UFO on a collision course with Earth. (It’s almost the exact same premise as “The Changeling,” a second season episode about an Earth probe that evolved into a killing machine.) The difference is entirely in the presentation of that premise. After a prologue in which the cloud (named V’Ger) destroys some Klingon warships, the movie shifts to Earth, where James T. Kirk, now an admiral chained to a desk at Starfleet Headquarters, uses this new threat to leverage himself back into command of the Enterprise. He demotes the Enterprise’s new captain, Willard Decker (Stephen Collins), and orders the ship out of Spacedock — but only after about 35 minutes of leisurely preamble.

Every aspect of the original Star Trek’s technology was about speed. The Enterprise’s warp engines allowed it to travel faster than the speed of light; its transporters could beam crew members across vast distances in the blink of an eye. The opening credits of each Star Trek episode showcased the Enterprise zipping around outer space. In ST: TMP, it takes Captain Kirk six minutes just to board to the damn ship on a shuttlecraft.

Once Kirk finally arrives and assumes command, he takes the ship into warp speed and its first action sequence: The new Enterprise suffers an engine glitch and careens into a wormhole, which is visualized onscreen with bleeding light and colors and everyone onscreen moving and talking really reeeeeeally slowly.

The line readings are so stilted — “Phoooootoooooon torrrrpeeeeeedooooos!” — they’re almost comical. Is Kirk trapped in a wormhole or is he doing an impression of Dory speaking whale? Star Trek: The Motion Picture may be the only production in Hollywood history where the action scenes actually slow the movie down. (And this thing didn’t exactly move like lightning to begin with.) In ST:TMP, even superluminal motion happens at a snail’s pace.

This is an observation, not a criticism. The movie moves slowly because it’s designed to move slowly. Star Trek: The Motion Picture, unlike so many blockbusters, is not engineered to work like an amusement park ride. It’s much more observational, like a guy considering an amusement park ride from a distance and admiring its aesthetic beauty. It imagines, in a way few science-fiction movies do, how the granular operation of a giant spaceship might actually work. It gets into the minutia of things like chain of command, bureaucracy, and technological errors. Exploring the galaxy in The Motion Picture isn’t fun; it’s a job. And it’s a pretty monotonous one sometimes.

You see it in both of the clips above; the way Scotty (James Doohan) takes Kirk up to the Enterprise in a roundabout way, not just to give the audience time to appreciate Douglas Trumbull’s incredible special effects, but because that is how traffic flows around the Enterprise while it’s parked. Observe the systematic way the Enterprise leaves Spacedock in the second clip; permission from dock control, maneuvering thrusters, thrusters at station keeping. Every order is given and then repeated. This is a movie about process. If Steven Soderbergh made a Star Trek, it might look a little like The Motion Picture.

(This attention to the mundane is why the uniforms, bland and boring as they are, make sense. What kind of military organization wears flashy multicolored regalia? These soft pastels and utilitarian jumpsuits fits the film’s more grounded approach to space travel and exploration.)

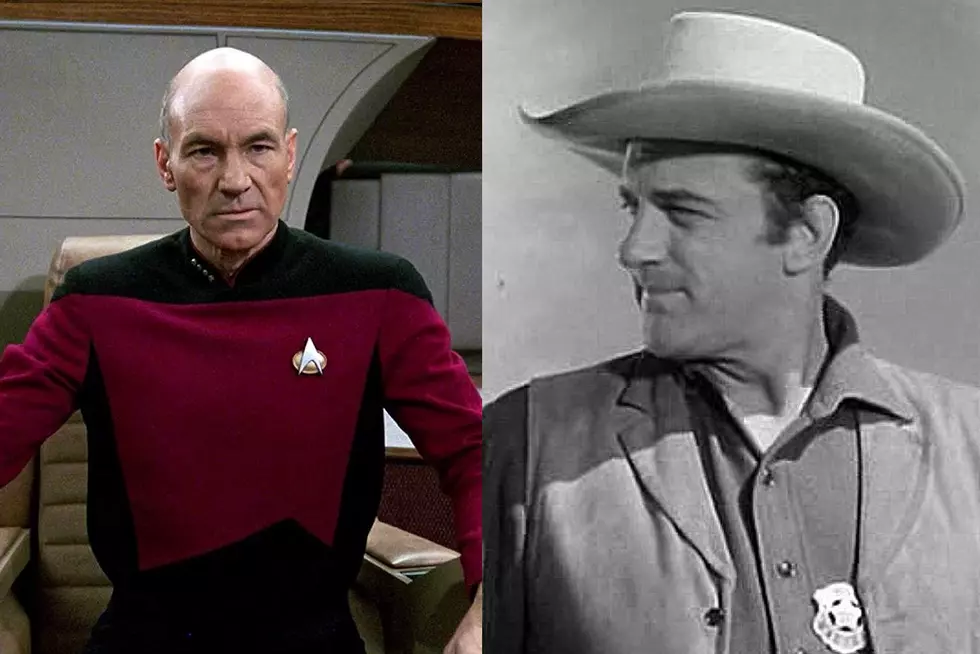

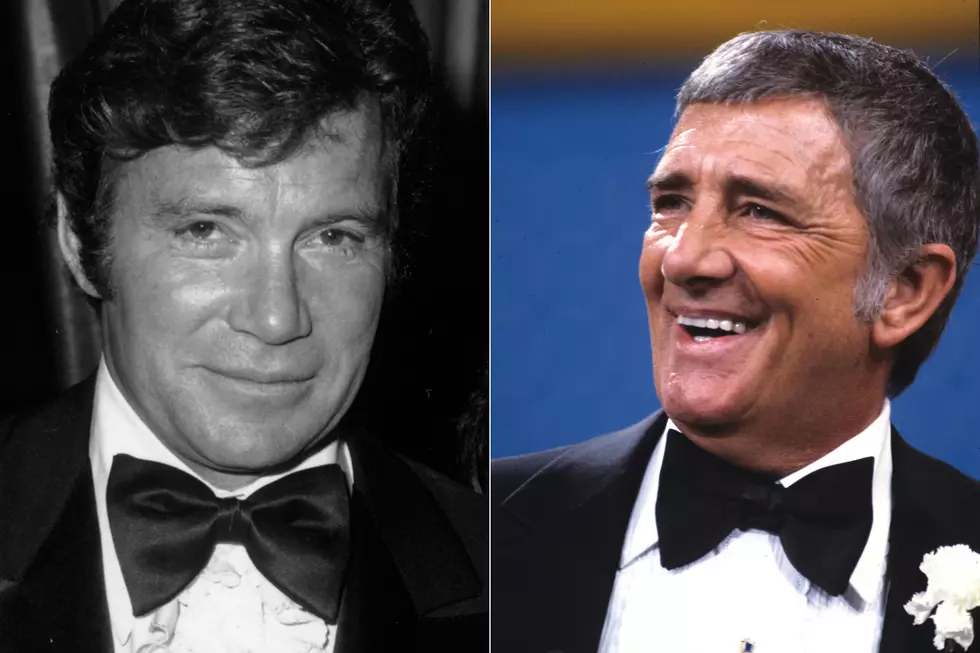

TMP’s meticulous structure also suits its characters. Now deep into middle age and a full decade removed from their final live-action TV appearance, Kirk, McCoy, and the rest are no longer the hotheaded cowboys of the original series. They’re getting older, and facing the frustrations and disappointments that come with that. They’re graying at the temples and sagging at the bellies. Kirk’s fitness to command is repeatedly challenged by Decker, who accuses him of being rusty. (He’s right, too.) Spock returns from a lengthy stint on Vulcan where he tried (and failed) to ritualistically purge all his human emotions. Dr. McCoy shows up for duty in a hobo beard and a giant astrosign medallion like he’s auditioning for a role in the crossover Grizzy Adams Meet the Wild and Crazy Guys in Space.

In this environment and with these characters, a breathless thriller would simply not make sense. One might even call director Robert Wise and producer Gene Roddenberry’s decision to match their film’s structure to their heroes’ temperaments entirely logical.

Even with a muted color palette, and even in the midst of a story about the sometimes tedious nature of outer-space life, Star Trek: The Motion Pictures has some truly gorgeous visuals. Wise takes full advantage of the widescreen frame, providing images that were never possible on the old Star Trek television show, and weren’t possible in many of the movies that followed, most of which were scaled down significantly from The Motion Picture, and occasionally shot on retrofitted television sets. As wonderful as the later movies were, they often felt like television shows projected on the big screen. Star Trek: The Motion Picture looks like a movie.

TMP also plays much better in a theater, where you can shut out the world and give yourself over completely to its hypnotic imagery. No wonder a generation of VHS and DVD viewers hate the film; it isn’t nearly as effective on home video. Once the Enterprise journeys inside V’Ger, the visuals get even more grand. These are some of the loveliest images the Star Trek franchise has ever produced:

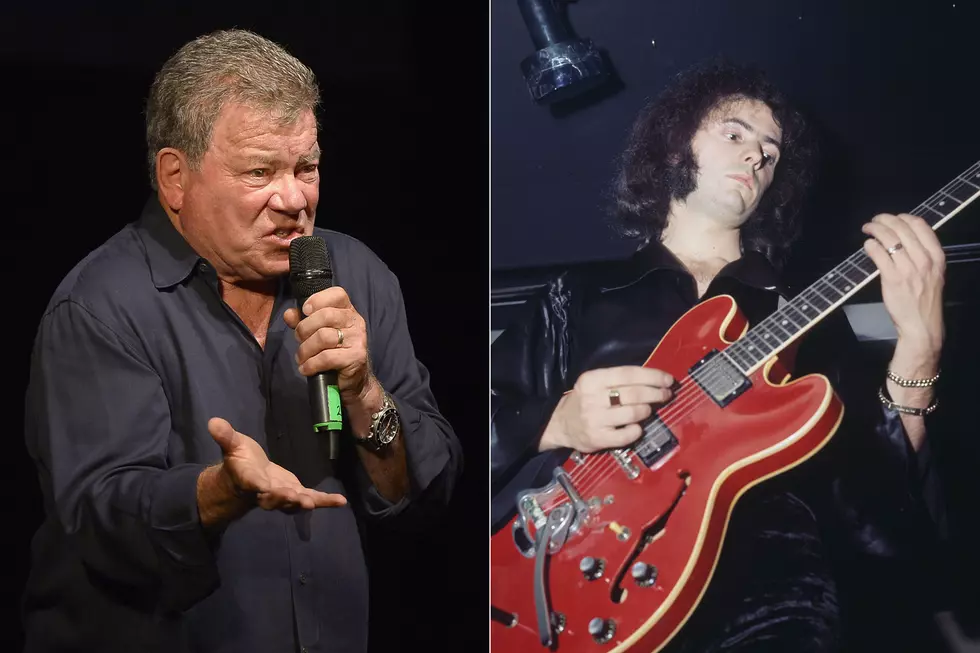

Also lovely: Jerry Goldsmith’s magnificent score for the film. His terrific theme later became the music under the opening credits of Star Trek: The Next Generation. In a widely derided film, this is probably the only universally beloved element:

What should also be beloved about The Motion Picture is the depiction of the relationship between Kirk and Spock, which is maybe the most tender of any in the Star Trek canon. Fans of Kirk/Spock need look no further than scenes like the ones below. The subtext here is so obvious it’s not even subtext.

These scenes mark a significant shift in the Spock character, who finally embraces his human side at the end of the movie. And they fit perfectly in TMP, which is largely a story of “simple feeling” about the importance of emotion in the grand scheme of the cosmos. In the end, what defeats V’Ger isn’t great weaponry or overwhelming power. It’s simple human love. Unfortunately, (SPOILER ALERT for the most famous Star Trek movie moment of all time) Spock got killed in the next movie, and the process of bringing him back to life basically erased all of his character development in The Motion Picture. One wonders if people would like TMP more if Star Trek II hadn’t ended in Spock’s death, and his evolution in The Motion Picture had been allowed to continue in future movies.

If you’re looking for someone to argue The Motion Picture is the best Star Trek movie with the original cast, you’ll have to look elsewhere. I still prefer The Wrath of Khan or the underrated The Undiscovered Country. As much as they fit in this context, the uniforms are so hideous (Why do they have belt buckles but no belts? Why?!?) that it’s sometimes hard to take the movie as seriously as it would like. I mean, look at that jackass security officer between Spock and Decker.

That guy’s supposed to maintain order on the bridge? He looks like he just came from playing laser tag. (My buddy and Trek fan supreme Jordan Hoffman says he looks like an extra who wandered out of the set of Spaceballs, and he’s absolutely right.)

In a recent interview with SFX Magazine, current Captain Kirk Chris Pine said he didn’t think “cerebral” Star Trek would work in “today’s marketplace.” “You can hide things in there,” he added. “Star Trek Into Darkness has crazy, really demanding questions and themes, but you have to hide it under the guise of wham-bam explosions and planets blowing up.”

Whether Pine is right or wrong is debatable. It’s inarguable, though, that the Star Trek movies he’s made have been less brainy than most of the ones from the previous cast. In fact, Pine’s Star Treks are way more like Star Wars than The Motion Picture, the Star Trek whose production was a direct result of Star Wars’ success. That doesn’t mean they’re necessarily bad; the first Pine Trek is enormously entertaining. Just that they’re a bit more ordinary, a bit more formulaic, and a lot less weird.

That’s all the more reason to celebrate Star Trek: The Motion Picture, which defied tradition at almost every turn and was a truly cerebral piece of science fiction on an epic scale. The Star Trek movies that followed were often much more conventionally entertaining. But they were rarely more formally adventurous.

Vulcan philosophy (and therefore Star Trek itself) is built on the concept of “infinite diversity in infinite combinations,” and one of the best things about this franchise after 50 years is the fact that the movies now reflect that diversity; there is a Star Trek movie for any mood or situation. If you want thrilling naval adventure, go with Wrath of Khan. If you want self-referential humor, pick The Voyage Home. If you want modern visual effects, try J.J. Abrams’ Star Trek. And if you’re in the mood to ponder man’s place in the universe while blissing out on amazing cinematic vistas, turn on Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

For more on Star Trek: The Motion Picture, listen to Matt Singer discussing the film with Jordan Hoffman on Engage: The Official Star Trek Podcast.

More From KKTX FM