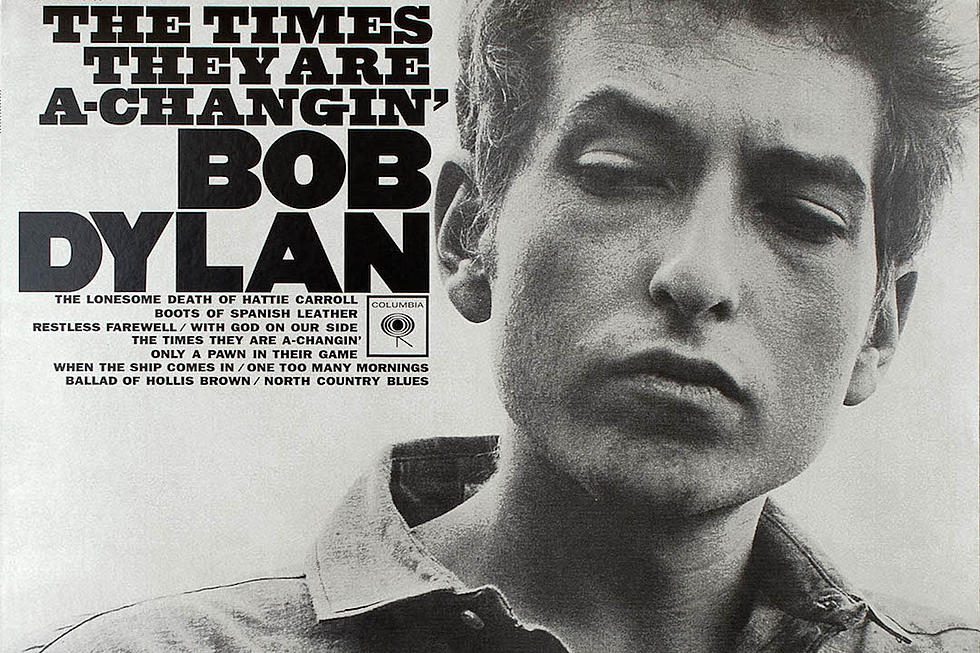

Bob Dylan’s ‘The Philosophy of Modern Song': Book Review

Bob Dylan offered a few thoughts on songwriting to The New Yorker in 1964, as sessions continued for his fourth studio album, Another Side of Bob Dylan. "Songs are so confining," the 23-year-old said. "Woody Guthrie told me once that songs don't have to rhyme – that they don't have to do anything like that. But it's not true. A song has to have some kind of form to fit into the music. You can bend the words and the meter, but it still has to fit somehow."

Even then, Dylan was considering how elements of songwriting could be combined to form a cohesive picture — and how he might be able to change, shift or sometimes do away entirely with those elements to write songs that would go on to become widely cited pillars of American music.

Now, six decades after the release of his debut album, Dylan is once again considering those elements. His newest book, The Philosophy of Modern Song, explores more than 60 tracks written and performed by other artists, ranging in style from Dean Martin's "Blue Moon" to the Clash's "London Calling." Most of the book's tidy chapters are split in two: The first half is dedicated to describing the song's characters and storyline theatrically, while the second half focuses on the song's real-life history and the explanation for why it works. It is, in essence, the closest we may ever come to a master class on songwriting from Dylan.

Along the way, Dylan helps readers understand why a song lands emotionally and offers some insight into his background, though he warns not to conflate the two. "Knowing a singer's life story doesn't particularly help your understanding of a song," he says when writing about Elvis Costello's "Pump It Up." "It's what a song makes you feel about your own life that's important."

Fans and journalists alike have been trying for decades to unravel the mercurial mystery that Dylan presents to the world. There aren't new answers to be found in The Philosophy of Modern Song. Dylan comes close to addressing some of the most hotly debated topics of his career — why he changed his name, why he continues to tour — but only via the stories of others. "Like with many men who reinvent themselves, the details get a bit dodgy," he writes in the chapter on "There Stands the Glass," sung by Webb Pierce.

The clearest example of this arrives midway through the book. "People confuse tradition with calcification," Dylan writes about the Osbourne Brothers' "Ruby (Are You Mad at Your Man)." "The recording is merely a snapshot of those musicians at that moment." For those who have been puzzled by Dylan's constant reimagining of his songs, therein lies at least part of the explanation. Elsewhere, Dylan's humor shines brightly. In the chapter on Johnnie Taylor's "Cheaper to Keep Her," he discusses marriage and divorce and ends up revealing polygamist sympathies for both men and women. "Have at it, ladies," he writes. "There's another glass ceiling for you to break."

You won't learn how to become a successful composer simply by reading The Philosophy of Modern Song. In the end, it is mainly a book designed for Dylan to discuss some of the tracks that have sparked his interest, curiosity and imagination over the years. He repeatedly implies that no official analysis of music should be taken without a grain of salt: "The argument can be made that the more you study music, the less you understand it." The Philosophy of Modern Song, then, is remarkable not because one of the most admired artists of his generation and beyond has weighed in on the work of others but because it proves a simple fact: Dylan loves music in the same way his fans do. "Music transcends time by living within it," he writes – and what a time to be alive.

Rejected Original Titles of 30 Classic Albums

Why Don't More People Like This Bob Dylan Album?

More From KKTX FM